A Clinician's Guide to MoCA Score Interpretation

Jan 5, 2026

Interpreting a MoCA score is far more art than science. While a score of 26 out of 30 is the widely recognized cutoff for "normal" cognitive function, that number is just the beginning of the story. It's a critical clue, not a conclusion.

Think of it as a single frame in a movie; it gives you a snapshot of cognitive function at one specific moment, but it doesn't reveal the whole plot. Understanding that single frame in the context of the entire film is where your clinical skill becomes invaluable.

Understanding the MoCA Score Beyond a Simple Number

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a fantastic first-line tool for flagging potential mild cognitive impairment (MCI). But its true clinical power is only unlocked when a clinician looks past the final tally and digs into the "why" behind it.

A score below 26 doesn't automatically mean dementia is present, just as a score at or above 26 doesn't give a clean bill of cognitive health. To get it right, you have to view the result through a much wider lens, one that brings the whole person into focus.

Here's a quick reference for the generally accepted score ranges.

MoCA Score Ranges at a Glance

Score Range | General Interpretation | Actionable Insights |

|---|---|---|

26-30 | Generally considered within the normal range for cognitive function. | Monitor annually. If the patient reports subjective memory issues, consider a more detailed digital cognitive assessment to establish a firm baseline for future comparison. |

18-25 | Suggestive of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). | Refer for comprehensive neuropsychological testing. Initiate blood work (B12, TSH) to rule out reversible causes. Begin a conversation about brain health lifestyle changes. |

10-17 | Suggestive of Moderate Cognitive Impairment, potentially Alzheimer's. | Conduct a safety assessment (driving, medication management). Connect the family with caregiver support resources. Schedule a family meeting to discuss long-term care planning. |

<10 | Suggestive of Severe Cognitive Impairment. | Shift focus to quality of life and symptom management. Ensure a safe living environment. Provide robust caregiver education and support for managing behavioral changes. |

This table provides a helpful starting point, but the real work of interpretation lies in understanding the individual patient.

Key Contextual Factors

To turn a raw number into a truly actionable insight, we have to consider the variables that can nudge a patient's performance up or down. These factors are absolutely crucial for avoiding misinterpretation.

Educational Background: This is a big one. The MoCA even has a built-in one-point adjustment for individuals with 12 or fewer years of formal education, recognizing how schooling can impact test performance.

Clinical History: A patient’s full medical history—things like depression, severe anxiety, or a recent stroke—can throw a wrench in the works and significantly affect their MoCA score.

Subjective Complaints: Never underestimate what the patient or their family is telling you. Their own reports of memory lapses or confusion add essential colour and context that a score alone will never capture.

A MoCA score is a signpost, not a destination. It simply points you in the right direction, flagging potential issues that demand a more thorough evaluation.

Practical Example: A 75-year-old retired engineer with 18 years of education scores a 26. His wife reports he's been forgetting appointments. This score, while technically "normal," is a significant concern because it likely represents a steep decline from his high intellectual baseline. The actionable insight here is to investigate further with advanced testing, not dismiss the concern based on the number alone.

For clinicians who want to sharpen their assessment skills, ongoing learning is key. To stay on top of best practices in this evolving field, you can explore additional training opportunities for clinicians and continue to refine your approach.

Breaking Down the MoCA Scoring System

To really get a handle on interpreting a MoCA score, you have to look under the hood at how it all works. It's tempting to just see the final number out of 30, but that's only the start of the story. Think of it less as a single grade and more as a composite sketch of a person's cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

The test is built to systematically check key cognitive functions, with each task having its own point value. This structure is what lets clinicians dig deeper than a simple "pass/fail" and start spotting patterns. This is where the real clinical insight begins.

The Seven Pillars of MoCA Assessment

The MoCA is designed to probe seven distinct cognitive domains. Understanding these pillars is the key to interpreting not just the final score, but how a patient got there. Losing a few points in one specific area tells a completely different story than losing points scattered across the board.

Here are the key areas the MoCA examines:

Visuospatial and Executive Functions: This is where you see the famous clock-drawing test and the cube copy task. Example: A patient scores full points on memory but loses 3 points on the clock draw (e.g., numbers outside the circle). This pattern doesn't scream "Alzheimer's" but might point toward issues with planning and organization, prompting you to ask about difficulties with tasks like managing finances.

Naming: The patient is simply asked to name three less-common animals (like a lion, rhinoceros, and camel). As straightforward as it sounds, this task is a great check for language ability and word retrieval.

Memory: A short-term memory task is a central piece of the puzzle. The administrator reads a list of five words, and the patient has to repeat them back right away and then again after a few minutes. This is a direct measure of how well their brain is encoding and retrieving new information.

Attention: This domain is tested with a few different tasks, like repeating a string of numbers forwards and backwards. Mistakes here can be a red flag for issues with concentration and working memory.

A common pitfall is getting fixated on the final score. The real gold is in the sub-scores. A patient who scores 25/30 but lost all their points on memory tasks presents a very different clinical picture from someone who also scored 25/30 but struggled with visuospatial items.

Scoring Nuances and Adjustments

The standard cutoff for what's considered "normal" cognition is a score of 26 or higher. But there's a critical rule you can't forget: the educational adjustment.

A one-point adjustment is added to the total score for anyone with 12 or fewer years of formal education. This is a crucial step to avoid penalizing someone whose performance might be more influenced by their educational background than by a true cognitive issue. For example, if a patient with 11 years of schooling scores a 25, their final, adjusted score becomes 26.

This foundational knowledge of the test's structure is absolutely essential for accurate interpretation. For a much deeper dive into the nuts and bolts of giving the test, check out our guide on MoCA assessment instructions. When you truly understand how points are awarded and lost, you can turn a simple number into a detailed cognitive snapshot.

What Else Shapes a MoCA Score?

A MoCA score is never just a number. It’s a snapshot of a person's performance on a specific day, under specific circumstances. To really understand what it means, we have to look beyond the score sheet and see the whole person.

Think of it like a standardized school test. A brilliant student might get a low mark if the test is in a language they don't speak fluently, but that says nothing about their actual intelligence.

Likewise, all sorts of personal and environmental factors can nudge a patient's MoCA performance up or down. Overlooking these is one of the biggest mistakes a clinician can make, sometimes leading to a misdiagnosis and a whole lot of unnecessary worry for the patient and their family. The real art of assessment is putting all these pieces together.

Education and Where They Started From

Education level is probably the most widely recognized factor that can sway a MoCA score. That's why the test itself includes a one-point bump for anyone with 12 or fewer years of formal education. But the truth is, education's impact is much more nuanced than a single point.

Imagine a retired professor with a PhD who has always been incredibly sharp. They score a 26, which technically falls in the "normal" range. But what if their baseline was always a perfect 30? In that context, a 26 could signal a meaningful decline.

Now, picture someone else with limited schooling who scores a 24. If their score stays stable every time they're tested, it might not point to a new cognitive issue at all. It's just their baseline. To get a better handle on how repeated testing helps build this picture, take a look at our guide on test and retest reliability.

Interpreting a score without knowing the patient's educational and occupational background is like trying to navigate without a map. The score tells you where you are, but the context tells you where you've come from.

Cultural and Language Biases

Someone's cultural background and how well they speak the language of the test are just as crucial. The MoCA was designed in a specific cultural setting, and some of the questions don't always translate perfectly. For example, the animal naming task might be tougher for someone who grew up in a place where camels or rhinos are unheard of.

This isn't just a small detail; it can lead to major disparities in who gets flagged for cognitive concerns. Research has shown that the standard MoCA cutoff can be way off the mark for certain groups.

One study found the standard cutoff of ≤26/30 correctly identified 73.2% of cognitively normal White participants.

But for Black participants, that same cutoff was only correct for 40.5% of cognitively normal individuals.

Researchers found that optimized thresholds showed a 3-point racial gap in average scores, pointing to a clear, built-in bias. You can read the full research about these MoCA findings to see the data for yourself.

These numbers are a stark reminder that a one-size-fits-all approach is dangerous. Clinicians have to dig deeper and gather this contextual information to avoid common pitfalls and make their assessments more accurate and fair.

Adjusting MoCA Interpretation for Diverse Populations

Trying to apply a single, rigid standard for MoCA scores across all individuals is like using the same ruler to measure a toddler and a basketball player—it just doesn't provide a meaningful measurement. The original normative data, which came out of a Canadian population, often doesn't capture the rich diversity we see in multicultural and multilingual communities. A "one-size-fits-all" approach can easily lead to serious misinterpretations.

This is exactly where sharp clinical judgment becomes so critical. A universal cutoff score can mistakenly label a huge portion of a perfectly healthy community as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI). A clinician’s real skill lies in their ability to adjust their interpretation based on a person's unique background, ensuring the assessment is both fair and accurate.

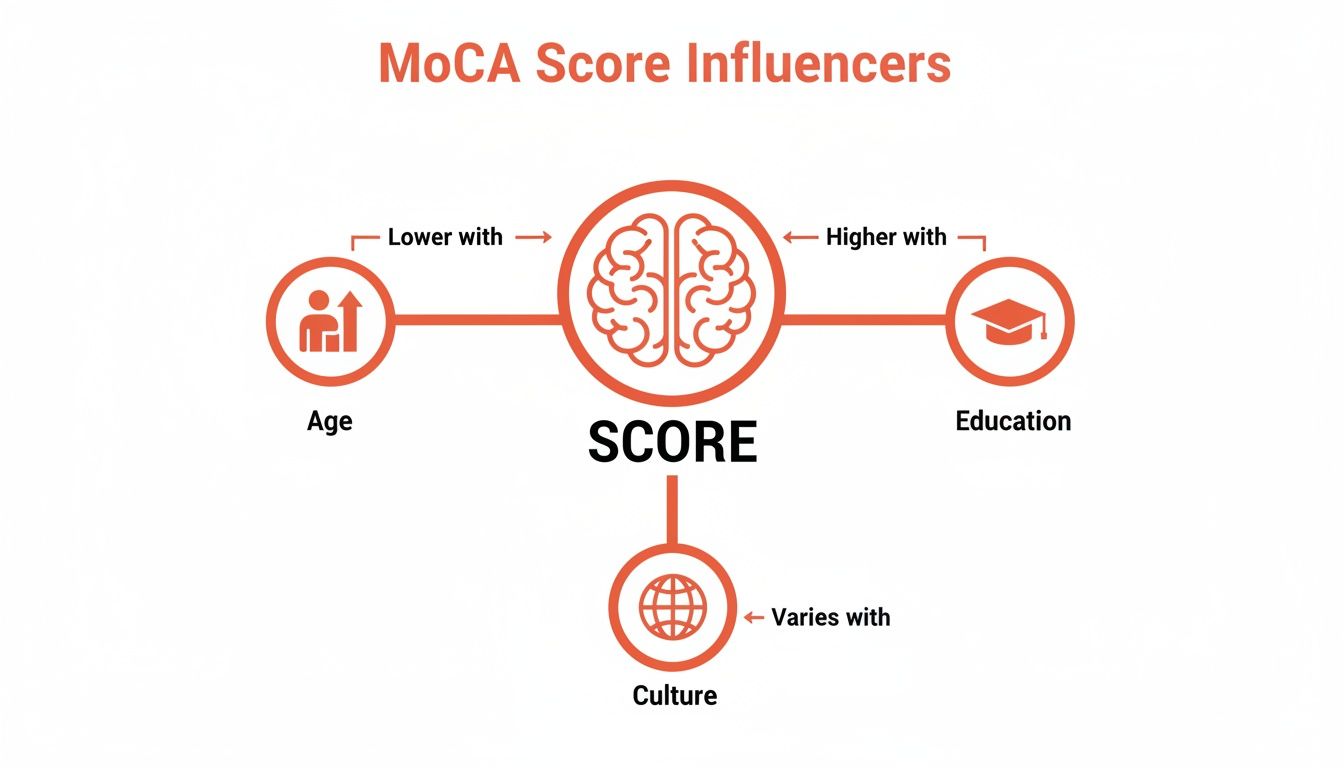

Think of it this way: a MoCA score isn't just a reflection of cognitive ability. It's influenced by several key factors.

As you can see, things like age, education, and cultural background aren't just minor details. They are powerful forces that can push a score up or down, demanding a much more flexible and thoughtful interpretation from us.

Beyond the Standard Cutoff

The problem with a standard cutoff score is well-documented in the field. A major population study based in Texas, for example, directly challenged the original Canadian MoCA cutoff of 26. The researchers discovered something startling: applying that strict score would have incorrectly flagged nearly half of their large, healthy community sample as having MCI.

This is a perfect illustration of the risk we run—over-pathologizing normal cognitive variations that exist within a diverse population.

Applying a universal standard without adjusting for demographics is a recipe for false positives. It creates needless anxiety for individuals and puts an unnecessary strain on the healthcare system to conduct follow-up testing.

This kind of research strongly supports what good neuropsychological testing has always done: use demographically adjusted norms. When you're looking at a MoCA score from someone in a diverse population, knowing how to apply and adjust for these reference points is essential. It's a fundamental part of using normative data effectively.

Factors Requiring Adjusted MoCA Interpretation

To make this more concrete, several key demographic factors require us to pause and consider how they might be shaping the score we see on the page. The table below breaks down some of the most common variables and the clinical considerations they demand.

Demographic Factor | Potential Impact on Score | Actionable Consideration |

|---|---|---|

Education Level | Lower formal education (especially <12 years) can negatively impact scores on tasks like abstraction and calculation. | Is the score a true reflection of cognitive decline, or does it mirror the person's educational baseline? The one-point adjustment is a start, but may not be enough. Compare to their functional abilities at home. |

Cultural Background | Items may be culturally biased (e.g., naming animals like a rhinoceros or a camel). Certain concepts may not translate directly. | Consider whether a specific item is unfamiliar due to cultural context rather than a cognitive deficit. Ask, "What would be a more common animal where you grew up?" to probe their knowledge base. |

Language & Literacy | Fluency in the test language is crucial. Low literacy can impact performance on reading and writing tasks. | Was the test administered in the person’s dominant language? Our guide on the language of assessment explores this in depth. |

Age | Older age is naturally associated with slightly lower scores on some cognitive tasks, even in healthy individuals. | Use age-adjusted norms whenever possible to compare the individual's score to their peers, rather than to a younger population. |

Socioeconomic Status | Can be linked to educational opportunities and familiarity with test-taking formats, indirectly influencing performance. | Look at the whole person. Consider their life experiences and occupation when evaluating their performance on tasks that require abstract thinking. |

Ultimately, this table reinforces a core principle: we must move beyond a simple numerical result and embrace a more holistic view of the individual being assessed.

Practical Scenarios for Adjusted Interpretation

So, what does this look like in the real world? It means stepping back from the score sheet and thinking critically about the person sitting in front of you.

Here are a couple of common scenarios:

The Recent Immigrant: A 68-year-old woman who recently immigrated scores a 23. She struggles with naming the rhinoceros and has a tough time with the abstraction task comparing a watch and a ruler. Actionable Step: Instead of an immediate MCI diagnosis, schedule a follow-up using a culturally adapted version of the MoCA or conduct the assessment with a professional interpreter. Your primary goal is to determine if the score reflects a cognitive issue or a cultural/linguistic barrier.

The Person with a Low-Literacy Background: A 72-year-old man with only an elementary school education, who has spent his entire life in manual labour, scores a 24 (before the one-point adjustment). Actionable Step: Focus on functional assessment. Ask his family specific questions: "Is he still managing his own bills correctly? Has he gotten lost while driving in familiar places?" If his daily functioning is intact, the score likely reflects his baseline, warranting monitoring rather than an aggressive workup.

By looking beyond a simple number and embracing a more nuanced, person-centred approach, clinicians can provide a far more accurate and equitable interpretation of a MoCA score.

Turning MoCA Scores Into Actionable Clinical Plans

A properly interpreted MoCA score is more than just a number; it’s the beginning of a conversation and a roadmap for what comes next. Its real value shines when it bridges the gap between a screening result and a clear, actionable clinical strategy.

Think of the score as the trigger for a series of logical next steps. It turns a single data point into a comprehensive care pathway, ensuring no concern is overlooked and every finding leads to a productive outcome.

From Score to Strategy: A Practical Framework

Different MoCA scores should prompt distinct clinical responses. A borderline result requires a very different approach than a score pointing to significant impairment. The key is having a framework ready to translate that number into a concrete plan.

Here’s how different scores might guide your clinical decisions:

A score of 24-25: This borderline result often calls for a "watch and wait" approach, but with active investigation. Actionable Plan: Schedule a follow-up assessment in 6 months. In the meantime, provide the patient with educational materials on brain health (diet, exercise, social engagement) and suggest they start a simple daily log of memory lapses to bring to the next visit.

A score of 18-23: When a score falls in this range, especially if the patient or their family reports a decline in daily function, it’s a much stronger signal. Actionable Plan: Refer for a full neuropsychological evaluation and order an initial lab panel (CBC, CMP, TSH, B12, Folate). Initiate a conversation about a formal driving safety evaluation if they are still driving regularly.

A score below 18: This points toward more significant cognitive challenges. The focus here naturally shifts toward safety assessments. Actionable Plan: Immediately discuss medication management solutions (e.g., pill organizers, family assistance). Provide the family with contact information for the local Alzheimer's Association or other caregiver support groups.

The MoCA is the starting point, not the finish line. It helps you ask the right questions; a full clinical workup provides the answers. A single score rarely tells the whole story on its own.

Building Personalized and Effective Care Plans

Once the MoCA flags a potential issue, the goal is to build a care plan that’s as detailed and personalized as possible. This means moving beyond the broad strokes of a screening tool to gather more precise cognitive data. The MoCA might tell you that there's a problem, but it doesn't always specify the exact nature or severity of the underlying deficits.

This is where more advanced digital assessment tools can come in handy. For example, Orange Neurosciences’ OrangeCheck platform provides objective cognitive profiles across multiple domains, including attention, memory, and executive function. This kind of precise data allows clinicians to pinpoint specific weaknesses and strengths, which is the foundation for truly targeted interventions.

By integrating these advanced assessments, you can move from a simple score to a robust, evidence-based plan. This approach not only helps in making a more accurate diagnosis but also in creating genuinely effective, personalized interventions. To see how these digital tools can fit into your practice, you can learn more about our cognitive therapies and how they support patient care.

Common MoCA Interpretation Questions Answered

Even when you feel you've got a good handle on the MoCA, tricky clinical situations pop up that can leave you scratching your head. This section dives into some of the most frequent questions we hear from clinicians about interpreting MoCA scores, offering straight-to-the-point, practical answers to help guide your next steps.

What Should I Do If a Patient Scores Just Below the Cutoff?

Think of a borderline score, like a 25, not as a red flag, but as a yellow one. It's a signal for careful clinical judgment, not immediate alarm.

Actionable Step: First, double-check the education adjustment. If it applies and brings the score to 26, document this and plan for routine annual screening. If the score remains at 25, your next action is to correlate it with function. Ask the patient and their family: "Have you noticed any recent changes in managing finances, medications, or navigating to familiar places?" If the answer is yes, proceed with a more detailed workup. If no, a "watchful waiting" approach with a re-test in 6-12 months is appropriate.

Ultimately, treat a borderline score as a call for heightened awareness and a more holistic look at the patient.

Can the MoCA Differentiate Between Types of Dementia?

In a word, no. The MoCA is a screening tool, brilliant for detecting that there might be a problem, but it’s not designed to be a diagnostic instrument for specific conditions like Alzheimer’s disease or Lewy body dementia. It tells you that cognitive impairment may exist, but it can't tell you what it is.

Practical Example: A patient scores 19/30, with significant point loss in visuospatial/executive function (e.g., poor cube copy, clock draw) but relatively preserved short-term memory. This pattern might suggest a non-Alzheimer's pathology, like Lewy body dementia, but it's only a hint. The actionable insight is to specifically mention this pattern in your referral to a neurologist, as it provides a valuable clue to guide their diagnostic investigation.

A low MoCA score is the trigger for a full diagnostic workup. That process is much more involved, typically including a complete neurological exam, blood work, neuroimaging, and often a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation to pinpoint the specific underlying cause.

The MoCA is like a smoke detector; it alerts you to a potential fire but doesn't tell you where it started or what's burning. Its purpose is to trigger the right emergency response—in this case, a thorough diagnostic process.

To get a better sense of how the MoCA stacks up against other screeners, take a look at our detailed comparison of the MoCA vs MMSE.

How Do Mood Disorders Like Anxiety Affect MoCA Scores?

Mood disorders can throw a real wrench in the works when it comes to MoCA performance. Depression, for example, can lead to what's sometimes called 'pseudodementia'—a state where cognitive symptoms like poor concentration, slow thinking, and memory lapses look strikingly similar to a neurodegenerative disease.

Actionable Step: If a patient has a low MoCA score, always administer a simple depression/anxiety screen like the PHQ-9 or GAD-7. If the results are positive for a mood disorder, the most appropriate next step is to treat the mood disorder first. Re-administer the MoCA in 3-6 months after the mood symptoms have improved. This prevents a premature and potentially incorrect diagnosis of a primary cognitive disorder.

Always consider the patient's mental and emotional state as a critical piece of the interpretive puzzle.

What Are the Best Supplements or Alternatives to the MoCA?

The MoCA is an excellent screener, but it shines brightest when it's part of a bigger assessment toolkit. No single test can ever give you the complete story of a person's cognitive health.

To build on what the MoCA tells you, clinicians have several options, depending on what they need to know:

For deeper insights: When a MoCA score is ambiguous or you need a more detailed profile, digital cognitive assessments are a fantastic next step. They can evaluate a wider range of cognitive domains with much greater precision, giving you objective data to back up your clinical decisions.

For tracking over time: To monitor a patient’s cognitive health longitudinally, digital platforms are ideal. Because they aren’t easily memorized like a paper test, they're perfect for retesting and establishing a solid baseline to track changes.

For a comprehensive view: When you suspect significant impairment, a full neuropsychological evaluation remains the gold standard for a definitive diagnostic workup.

A tiered approach is often the best practice. Use the MoCA to flag individuals who might be at risk, then turn to more advanced digital tools for deeper insights and to build truly personalized care plans.

At Orange Neurosciences, we provide clinicians with advanced digital tools that go beyond screening. Our platform delivers objective cognitive profiles to help you make faster, better-informed decisions and build truly personalized care plans. Discover how we can support your practice at https://orangeneurosciences.ca.

Orange Neurosciences' Cognitive Skills Assessments (CSA) are intended as an aid for assessing the cognitive well-being of an individual. In a clinical setting, the CSA results (when interpreted by a qualified healthcare provider) may be used as an aid in determining whether further cognitive evaluation is needed. Orange Neurosciences' brain training programs are designed to promote and encourage overall cognitive health. Orange Neurosciences does not offer any medical diagnosis or treatment of any medical disease or condition. Orange Neurosciences products may also be used for research purposes for any range of cognition-related assessments. If used for research purposes, all use of the product must comply with the appropriate human subjects' procedures as they exist within the researcher's institution and will be the researcher's responsibility. All such human subject protections shall be under the provisions of all applicable sections of the Code of Federal Regulations.

© 2025 by Orange Neurosciences Corporation