A Practical Clinician's Guide to MoCA Assessment Instructions

Dec 3, 2025

Administering the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a standardized process, but it's much more than just a checklist. The 30-point test typically takes about 10-15 minutes, and a certified clinician's guidance is key to navigating the tasks that touch on everything from visuospatial skills to memory, attention, and executive function. It’s our best tool for screening for mild cognitive impairment, and following the instructions precisely is what makes it so powerful.

Laying the Groundwork for an Accurate MoCA

Before you even pick up a pencil, it's crucial to appreciate what the MoCA truly is. This isn't just another form to fill out during an appointment; it's a finely tuned instrument designed to catch the subtle cognitive shifts that other screeners often miss. Think of it as a reliable snapshot of a person's cognitive health at a specific moment in time.

The MoCA has become a clinical go-to for one big reason: its incredible ability to spot mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Its sensitivity is what truly sets it apart. While the older Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) has a sensitivity of only about 18% for MCI, the MoCA boasts a sensitivity of 90%. That’s a massive leap in our ability to detect issues early, which is everything when it comes to timely intervention. You can learn more about the research behind the MoCA on the MoCA Cognition official site.

The Non-Negotiable Prerequisites

To use the MoCA correctly and ethically, a few things are absolutely mandatory. First and foremost is official training and certification through MoCA Cognition. This isn't just a suggestion—it's a requirement to ensure you grasp the standardized instructions, the nuances of scoring, and how to apply it in a clinical setting. Administering the test without certification is a copyright violation, and more importantly, it risks inaccurate results and poor clinical judgment.

Just as important is the environment. The assessment space has to be right:

Quiet and Private: No TVs, hallway chatter, or ringing phones. Practical example: If you're in a busy clinic, find an unused office or exam room and put a "Do Not Disturb" sign on the door.

Free of Distractions: Keep the area clear of clutter that could pull focus. Actionable insight: Remove promotional pamphlets, medical charts, and even family photos from the patient's line of sight.

Well-Lit and Comfortable: Good lighting and a comfortable chair can make a world of difference, preventing fatigue that could easily skew the results.

Assembling Your Assessment Toolkit

Walking into a session unprepared can throw things off before you even begin. Having all your materials ready isn't just about professionalism; it ensures a smooth, focused process for both you and the patient. A simple checklist can be a lifesaver.

Actionable Insight: When your materials are organized, you can dedicate your full attention to the patient—their performance, their comfort, and their non-verbal cues. This is where you pick up on the subtle qualitative observations that give the final score its true clinical meaning.

Here’s a quick list of what to have on hand:

The Official MoCA Test Form: Always use the current, official version you get after certification. Using different versions for re-testing helps minimize practice effects.

A Blank Sheet of Paper: For the patient’s drawings and written tasks.

Two Pencils with Erasers: One for the patient and a spare for you.

A Stopwatch or Timer: For the timed subtasks, a dedicated timer is far more reliable than your phone.

Before we dive into the specifics of the test itself, it's helpful to see how all the pieces fit together. Here's a quick overview of what the MoCA covers.

MoCA Test At-a-Glance

Component | Description |

|---|---|

Visuospatial/Executive | Tasks like trail-making, cube copying, and clock drawing to assess planning and visual perception. |

Naming | Identifying common animals to check language abilities. |

Memory | Immediate recall and delayed recall of a short list of words. |

Attention | Digit span forward and backward, vigilance (tapping on a specific letter), and serial subtraction. |

Language | Sentence repetition and verbal fluency (naming words that start with a specific letter). |

Abstraction | Identifying the conceptual link between two words (e.g., train-bicycle). |

Orientation | Stating the date, month, year, day, place, and city to assess orientation to time and place. |

This foundational knowledge helps transform the MoCA from a routine task into a powerful clinical interaction. Understanding the why behind the steps is just as important as knowing the how. To place this tool within a larger framework, our guide on what is a cognitive assessment offers more context. With this preparation, you’re set up for a valid, reliable, and patient-centred evaluation every single time.

A Practical Walkthrough of MoCA Administration

Administering the Montreal Cognitive Assessment is much more than just reading questions off a form. It's a clinical skill, a delicate balance of standardized procedure and genuine human connection. The real goal is to build rapport and create a comfortable space where a patient's cognitive abilities can be accurately reflected.

This walkthrough is designed to give you practical, task-by-task guidance to help you run a smooth and effective MoCA every single time.

First things first: preparation. Getting everything in order before the patient is in front of you is non-negotiable. It means your focus can be entirely on them, not on finding a pencil or silencing a buzzing phone.

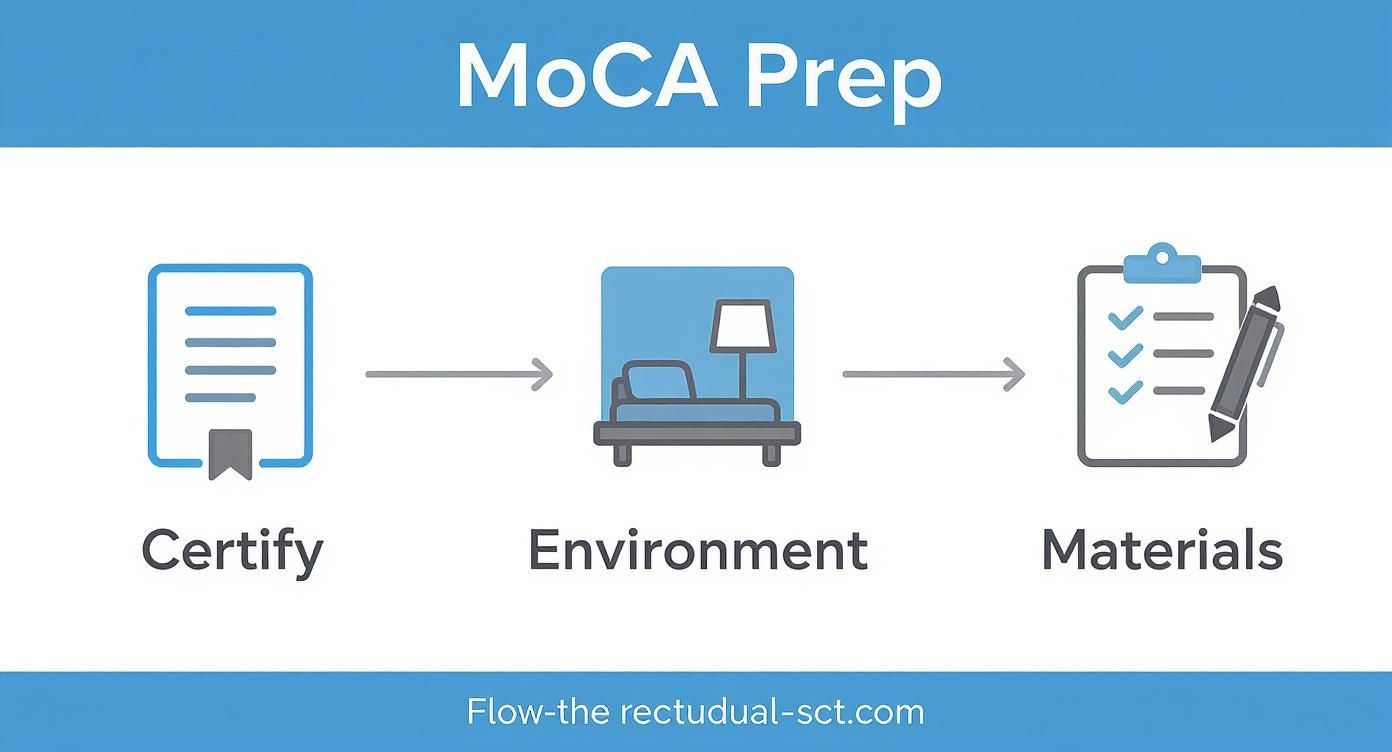

This simple flowchart breaks down the critical prep work.

Think of these as the three pillars of a valid assessment: proper certification, a controlled environment, and having all your materials ready to go.

Navigating the Visuospatial and Executive Function Tasks

The assessment kicks off with tasks that can sometimes feel a bit intimidating. How you introduce them is key to minimizing anxiety and getting a response you can actually score.

Take the Trail Making Test. Instead of a blunt, "Connect the number to the letter," try a softer, more practical approach. Something like: "This first task is a bit like a puzzle. I’d like you to draw a line, going from a number to a letter in order. You’ll start at 1 and go to A, then to 2 and then to B, and so on, until you reach the end at E. Please try not to lift your pen from the paper."

What if they make a mistake but catch it right away? The standard protocol is clear: you don't deduct a point for a self-corrected error. Actionable insight: You should absolutely note the self-correction in your qualitative observations. It's clinically significant and can point to intact self-monitoring skills.

Introducing the Cube Copy and Clock Draw

The drawing tasks are often where patient anxiety can really spike. You’ll frequently hear, "Oh, I'm not an artist," or "I haven't drawn anything in years." It's essential to be reassuring.

For the Cube Copy, a simple, "Just do your best to copy this drawing. It doesn’t need to be perfect," can work wonders. After all, a perfect drawing isn't the goal. The task is assessing visuospatial and executive skills. A scorable cube simply needs to have three dimensions, all lines present, no extra lines, and for the lines to be relatively parallel and of similar length.

The Clock Drawing Task is particularly sensitive to how you frame it. You need to be crystal clear to avoid confusion.

Practical Scripting Tip: "Now, I'd like you to draw a clock. First, draw the circle, put in all the numbers, and then set the hands to show the time 'ten past eleven'."

Breaking it down into three distinct commands prevents the patient from feeling overwhelmed and ensures you can accurately score the three separate points for this item: one for the contour (the circle), one for the numbers, and one for the hands.

Assessing Memory and Recall with Nuance

The memory section seems straightforward on the surface, but how you manage it directly impacts its validity. When you present the five words for recall, the script is precise for a reason: "I am going to read a list of words that you will have to remember now and later on. Listen carefully. When I am through, tell me as many words as you can remember."

Important Considerations for Memory Tasks:

No Cues on the First Trial: Never provide hints or clues during the immediate recall attempts.

Repetition: You read the list twice. Remember to check the box for the second trial to confirm you did it.

Delayed Recall: This comes near the end of the assessment. When you ask for the delayed recall, do not re-read the words. If the patient is struggling, then you can offer category cues (e.g., "One of the words was a part of the body"). If they still can't recall, you can offer a multiple-choice cue (e.g., "Was the word FACE, HAND, or LEG?"). Critically, you must mark any cues used on the scoring sheet, as this affects the final score.

Handling Abstraction and Language Fluency

The abstraction task asks the patient to find the similarity between two items, like a "train and bicycle." It’s common for patients to give concrete answers here instead of abstract ones.

Practical example: If a patient says, "They both have wheels," that's a concrete answer and scores 0 points. The correct, abstract answer would be something like, "They are both modes of transportation." If you get a borderline answer, you're allowed to prompt once by saying, "Tell me another way they are alike." Just be careful not to over-prompt, as that can invalidate the response.

Finally, the verbal fluency task—where the patient has one minute to name as many words as possible beginning with a specific letter—is a timed test of executive function. Have your timer ready. Start it the moment you say the letter. Remember not to score proper nouns, numbers, or different forms of the same verb.

By approaching each task with thoughtful scripting and a deep understanding of common patient responses, you can maintain standardization while still fostering a supportive environment. This human-centred approach is the key to gathering accurate data. As you get more comfortable, you might find that digital tools can help streamline this process. To learn more about that landscape, you can explore our guide to conducting a cognitive assessment online.

How to Score and Interpret MoCA Results Accurately

Once you've administered the test, the real clinical work begins. Getting the score right is crucial, but true insight comes from interpreting the patterns of errors you observed and the qualitative notes you took along the way. The MoCA isn't just a number; it's a window into your patient's cognitive world.

This process is far more than just tallying points. It demands sharp clinical judgment, particularly for the tasks that aren't a simple right or wrong. Let’s dive into how to score these sections with the precision they require.

Scoring the Subjective Tasks

Items like the cube copy and clock draw are famously subjective, which is why sticking to the official scoring criteria is non-negotiable for the test's validity.

Cube Copy Scoring (1 point): To award the single point here, the drawing has to tick all the boxes. It must be:

Three-Dimensional: It should look like a cube, not just two squares overlapping.

All Lines Present: Every single line from the example must be there.

No Extra Lines: The patient can't add any extra lines to their drawing.

Reasonably Proportional: We aren't looking for an artist's rendering, but the lines should be relatively parallel and of similar length. The overall shape needs to be intact.

A drawing that looks flat, is missing lines, or is wildly distorted gets 0 points. Actionable insight: Pay close attention to how they drew it. Did they tackle it systematically, or did they draw it piece by piece without a clear plan? This can give you valuable clues about their executive functioning. Our guide on how to test for executive dysfunction offers more context on this.

Clock Drawing Scoring (3 points): This task is a goldmine of information, broken down into three distinct points.

Contour (1 point): The circle itself needs to be mostly complete and round. Minor distortions are okay, but it should be a closed shape.

Numbers (1 point): All numbers from 1 to 12 must be present, in the right order, with no duplicates. Roman numerals don't count here.

Hands (1 point): The patient must draw two hands that clearly show 'ten past eleven'. This means the hour hand must point directly at the 11 and the minute hand at the 2.

One of the most common errors I see is the hour hand pointing to the 10. That small mistake costs the patient the point for the hands and can signal subtle deficits in planning and attention.

Applying the Education Adjustment

This next step is absolutely critical and often overlooked. You must add one point to the total score for any individual who has 12 years or less of formal education.

Actionable Insight: This isn't just a suggestion; it's a required part of the scoring protocol. Forgetting to add this point can incorrectly flag a healthy individual for cognitive impairment, leading to unnecessary stress or, conversely, delay follow-up for someone who is truly within the normal range for their education level.

Practical example: Think about a patient who scores 25 and has a high school diploma but no post-secondary education (12 years). A score of 25 falls just under the typical cutoff of 26, suggesting possible MCI. But once you apply the one-point adjustment, their score becomes 26, placing them squarely in the normal range. It makes a huge difference.

Moving Beyond the Total Score

The final number is just the start of the conversation. While a score of 26 out of 30 is the generally accepted cutoff for normal cognition, this number means nothing without the full clinical context.

Look at the error patterns. Did the patient lose all their points on memory-related tasks? Or were the mistakes clustered in the executive function and visuospatial domains? Analyzing where the points were lost helps you build a working hypothesis about the potential cognitive impairment.

The MoCA score also has real-world implications. One study with 127 patients found that a score of 22 correlated with a 75% probability of having the capacity to make their own medical decisions. That probability plummeted to just 24% for patients who scored 15.

Ultimately, interpreting the MoCA is an art informed by science. The total score, your qualitative observations, and the patient's history all come together to paint a picture that will guide your next steps—whether that's offering reassurance, ordering further tests, or making a specialist referral.

Handling Common Assessment Challenges and Adaptations

Even the most perfectly prepared assessment can hit a snag. Real-world clinical practice is messy. Patients come with their own unique histories, sensory limitations, and anxieties, and your ability to adapt on the fly is just as crucial as following the script. This is your guide to navigating those common bumps in the road while protecting the validity of the MoCA.

Successfully navigating these situations isn’t just about getting a score; it’s about gathering accurate data while maintaining a supportive, patient-centred environment. The goal is to accommodate the person in front of you without compromising the standardized nature of the test.

Adapting for Vision and Hearing Loss

Sensory impairments are incredibly common, especially in the populations we often screen. Without thoughtful adjustments, you risk measuring a sensory deficit rather than a cognitive one, which muddies the waters completely.

For a patient with significant vision loss:

You’ll need to read all instructions aloud, and that includes the instructions for the visuospatial tasks.

Verbally guide them through the trail-making task. Practical example: "From number 1, you will draw a line to the letter A..."

The cube and clock drawing portions can be omitted, but you absolutely must document this modification and the reason why. It’s critical to remember that you do not award points for any omitted items.

For a patient with hearing loss:

Make sure you’re facing them directly. Speak clearly and a little slower than you normally would.

Do what you can to minimize background noise. If a hearing amplifier is available and the patient is comfortable with it, use it.

A large-print version of the test can be a huge help, allowing them to read along as you give verbal instructions.

Any adaptation, no matter how small it seems, needs to be meticulously documented in the patient’s file. This gives crucial context to anyone who looks at that score down the line.

Managing Language Barriers and Patient Anxiety

Language differences can be a major hurdle. It is absolutely critical to use an official, validated translation of the MoCA in the patient's primary language. Don’t try to translate on the spot—you’ll invalidate the results. Nuances in language and culture are baked into these cognitive tasks. To dive deeper, check out our detailed guide on the language of assessment.

Patient anxiety is another performance killer. A patient who feels stressed, rushed, or judged will likely struggle with attention and memory, tainting the results.

Actionable Insight: A simple, reassuring statement like, "This isn't a pass-or-fail test. We're just getting a snapshot of how your brain is working today," can make a world of difference. Your calm, supportive demeanour is one of your most effective clinical tools.

If a patient becomes overly anxious or fatigued, it's perfectly fine to take a short break. Just document the pause and resume when they feel more comfortable. This small act of compassion can salvage an assessment that might otherwise be compromised by distress.

A quick-reference guide can be helpful for remembering how to handle these common situations while maintaining the integrity of the test.

MoCA Adaptation Quick Guide

Barrier | Recommended Adaptation | Documentation Note |

|---|---|---|

Vision Loss | Read instructions aloud; verbally guide drawing tasks. Omit drawing sections if necessary. | "Cube and clock drawing omitted due to severe visual impairment (macular degeneration). No points awarded." |

Hearing Loss | Face patient directly, speak clearly, reduce background noise. Use a large-print version for them to follow. | "Administered in a quiet room with patient using personal hearing aid. Patient confirmed understanding." |

Language Barrier | Use an official, validated translation of the MoCA. Do not attempt to live-translate the test. | "Administered using the official [Language] version of MoCA [Version #]." |

Anxiety/Fatigue | Offer reassurance and provide a short break if needed. Maintain a calm, unhurried pace. | "Brief (5-min) break provided after Serial 7s due to patient-reported anxiety. Assessment resumed." |

Keeping these adaptations in mind ensures you're assessing cognition, not a patient's ability to overcome a sensory or emotional barrier.

Embracing Telehealth Administration

Telehealth has opened up access to cognitive screening like never before, but it brings its own unique challenges to the table. The good news? The MoCA has been validated as a reliable tool for remote administration. In fact, research confirms the MoCA's validity across cognitive domains, showing no significant performance differences between online and in-person formats. You can read the full research about these telehealth findings for a deeper dive.

To ensure a valid telehealth assessment, a little prep goes a long way:

Confirm they have a stable internet connection and that their audio and video are working well before you start.

Instruct the patient to be in a quiet, private room where they won't be interrupted.

Have them show you their workspace with their camera to confirm they don't have notes or other aids nearby.

For the drawing tasks, instruct them to hold their completed drawings up clearly to the camera for you to score.

Navigating these real-world complexities is a core clinical skill. By thoughtfully applying these adaptations, you can uphold the integrity of the MoCA and gather meaningful data that truly reflects your patient’s cognitive status. The next step is integrating these findings into a cohesive care plan, which we’ll explore by looking at documentation and your broader clinical workflow.

Integrating MoCA Results Into Your Clinical Workflow

The assessment isn't really over when the patient leaves your office. A MoCA score is only as valuable as its role in the patient's ongoing care, and that process starts with clear, comprehensive documentation that tells the whole story.

Your final note should be a clinical narrative, not just a number dropped into a chart. It needs to provide enough context for any colleague to understand the result at a glance. Think beyond the total score and dig into the specific details that informed your clinical judgment.

Crafting a Complete Patient Record

A well-crafted note transforms the MoCA from a simple screening tool into a foundational piece of the patient's health record. I always make sure my documentation includes these key elements:

Final Score and Adjustments: Clearly state the total score. It's also crucial to specify if the one-point education adjustment was applied. Practical example: "MoCA score: 25/30; +1 point for 12 years of education, adjusted score: 26/30."

Qualitative Observations: Document how the patient approached the tasks. Did they self-correct? Show signs of frustration or anxiety? Take an unusually long time on one specific section? These observations add critical colour to the final score.

Domain-Specific Performance: Briefly note any patterns you observed. Practical example: "Patient lost 4/5 points in delayed recall but scored perfectly on executive function tasks." This detail is far more useful than the total score alone.

Modifications Made: Detail any adaptations you made for sensory or other limitations. A good example is noting the omission of drawing tasks due to severe visual impairment.

Understanding MoCA Licensing and Certification

Using the MoCA comes with professional responsibilities. It’s a copyrighted tool, and its use in clinical practice is contingent upon completing the mandatory training and certification provided by MoCA Cognition.

This isn't just a box to tick; it ensures every administrator understands the standardized moca assessment instructions and scoring nuances that protect the test's validity. Using unofficial copies or administering the test without certification is a copyright violation that ultimately compromises patient care.

Actionable Insight: A certified administrator is the cornerstone of a valid assessment. This training ensures that the MoCA is used consistently and ethically, providing reliable data that can confidently guide clinical decisions and improve patient outcomes.

Connecting Results to Long-Term Care

The final, and most important, step is turning these findings into action. A MoCA score is a powerful piece of data that can inform treatment plans, guide referrals, and establish a baseline for tracking cognitive changes over time.

This is where digital health platforms become indispensable. By integrating MoCA results into a system like the one offered by Orange Neurosciences, you create a seamless bridge between assessment and intervention. It allows you to translate raw data into dynamic, long-term cognitive care plans. Our guide to ensuring continuity of care explores how these connections improve patient outcomes.

To further streamline this process, you might find valuable insights in general strategies for improving workflow efficiency, which can help you manage and act on clinical data more effectively. By building a robust workflow, you ensure every assessment leads to meaningful, proactive care.

Common Questions We Hear About the MoCA

Even with the best instructions, some questions always come up in the day-to-day reality of a busy practice. Let's walk through some of the most common queries we get from clinicians, with practical answers to help you navigate the MoCA with confidence.

Think of this as your go-to reference for those tricky situations that the manual doesn't always cover.

How Do I Handle a MoCA for a Patient Who Speaks a Different Language?

This is a situation where you absolutely have to stick to the script. The only valid way forward is to use an official, validated translation of the MoCA test in the patient's primary language. You can get these directly from MoCA Cognition once you've completed the required certification.

Whatever you do, don't try to translate the test yourself or use an interpreter on the fly. This immediately invalidates the results. The linguistic and cultural subtleties of the test items are incredibly specific and get lost in translation, rendering the score meaningless.

Actionable insight: If an official translation isn't available for that language, the best course of action is to document this limitation in the patient's chart and consider referring them to a clinician who can administer a culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment.

Can I Administer the MoCA Without Official Training?

The short answer is a hard no. The MoCA is a copyrighted clinical instrument, and its use is contingent on completing the mandatory training and certification. This isn't just a bureaucratic hurdle; it's a matter of clinical ethics and patient safety.

The certification process is what ensures you understand the nuances of the standardized MoCA assessment instructions, the subtle scoring rules, and how to properly interpret the results. Attempting to administer it without this foundation can easily lead to incorrect scores and flawed clinical judgments, which defeats the entire purpose of the assessment.

Adhering to the certification requirement protects the integrity of the test itself. But more importantly, it ensures every patient receives an assessment that is both valid and reliable. It’s simply a cornerstone of good clinical practice.

What’s the Next Step if a Patient Scores Below 26?

A score below the typical cutoff of 26 is a significant finding, but it is not a diagnosis. Think of it as a clear signal that a deeper investigation is warranted.

Your immediate next step should be to plan a comprehensive diagnostic workup to figure out what's behind the score. This process usually involves a few key components:

A detailed neurological exam.

Lab work to check for reversible causes of cognitive changes, like vitamin B12 deficiency or thyroid issues.

More advanced neuroimaging, such as an MRI.

A referral to a specialist—perhaps a neurologist, geriatrician, or neuropsychologist—for a more in-depth evaluation.

The MoCA gives you the "what"—the indication of cognitive impairment. The follow-up workup is what helps you discover the "why."

At Orange Neurosciences, we know that a cognitive assessment is just the starting point. Our AI-powered platform helps you translate MoCA results into meaningful, long-term care plans, backed by objective data and real-time support for your clinical decisions. Learn how you can bridge the gap between assessment and intervention by exploring our solutions at https://orangeneurosciences.ca. For a personalized consultation, feel free to contact our team via email or visit our website today.

Orange Neurosciences' Cognitive Skills Assessments (CSA) are intended as an aid for assessing the cognitive well-being of an individual. In a clinical setting, the CSA results (when interpreted by a qualified healthcare provider) may be used as an aid in determining whether further cognitive evaluation is needed. Orange Neurosciences' brain training programs are designed to promote and encourage overall cognitive health. Orange Neurosciences does not offer any medical diagnosis or treatment of any medical disease or condition. Orange Neurosciences products may also be used for research purposes for any range of cognition-related assessments. If used for research purposes, all use of the product must comply with the appropriate human subjects' procedures as they exist within the researcher's institution and will be the researcher's responsibility. All such human subject protections shall be under the provisions of all applicable sections of the Code of Federal Regulations.

© 2025 by Orange Neurosciences Corporation