ADL vs IADL A Clinician's Guide to Functional Assessment

Dec 28, 2025

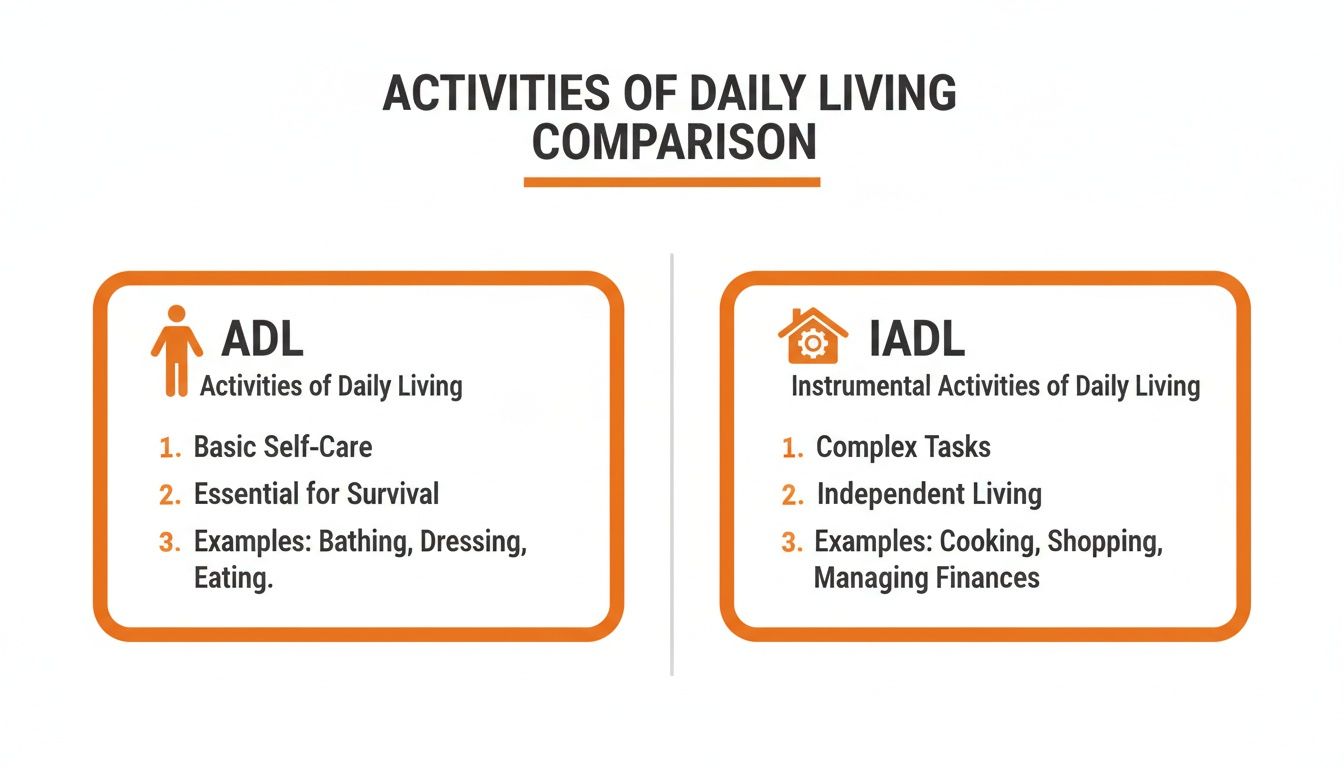

When we talk about a person's ability to live on their own, the terms ADL and IADL are fundamental. The core difference is straightforward: Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are the basic tasks of self-care, like bathing and dressing. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) are the more complex skills someone needs to live independently within a community, like managing their finances or cooking a meal.

Grasping this distinction is more than just clinical semantics; it’s a critical piece of the puzzle for spotting the early signs of cognitive or functional decline. It's the key to creating actionable care plans that make a real difference.

Understanding the Core Functional Differences

Clinicians and caregivers rely heavily on the ADL vs. IADL framework to evaluate a person’s functional capacity. Think of them as two distinct but interconnected layers of independence. Each category gives us crucial insights into an individual's overall well-being and ability to navigate their world safely.

ADLs are the essential, foundational skills we need to manage our own bodies—the kind of tasks we learn as young children that are vital for survival. A practical example is the ability to feed oneself, which involves the physical act of bringing food to the mouth.

IADLs, on the other hand, demand a higher level of thinking. They require more complex cognitive processes like planning, organising, and problem-solving. A related IADL would be preparing a meal, which involves planning what to eat, shopping for ingredients, and following a recipe.

This chart breaks down the differences visually, making it easy to see how these two categories compare.

As the chart shows, ADLs are really about personal survival. IADLs are about interacting with the wider environment to maintain a household and participate in community life.

ADL vs IADL Key Distinctions at a Glance

For a quick reference, the table below highlights the fundamental differences between these two crucial areas of function. It's a handy way to see their distinct roles in assessing independence.

Attribute | Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) |

|---|---|---|

Core Focus | Basic Self-Care & Survival | Community Independence & Household Management |

Complexity | Simple, routine tasks | Multi-step, complex tasks requiring planning |

Cognitive Load | Lower cognitive demand | Higher cognitive demand (executive function) |

Common Examples | Bathing, dressing, toileting, mobility | Managing finances, cooking, transportation, medication |

Timing of Decline | Difficulties often appear in later stages | Difficulties often appear in earlier stages |

Looking at the table, it becomes clear why a decline in IADL performance often rings the first alarm bell for cognitive impairment. Tasks like managing medications or using public transit require high-level executive functions, which are frequently among the first skills to be affected by conditions like dementia.

Research from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) backs this up. The study found that while 12.5% of participants showed some dependence in basic ADLs, a significantly higher 28.3% reported difficulties with IADLs. This data offers a powerful look at how these abilities can change as we age.

This disparity underscores a critical clinical insight: challenges with IADLs often precede noticeable ADL decline, offering a crucial window for early detection and intervention.

Understanding this progression is essential for building effective care plans. It’s why many structured evaluations, including various occupational therapy assessments, are specifically designed to pinpoint these subtle but incredibly significant changes in a person's functional abilities.

A Nuanced Comparison of Everyday Functional Activities

To really get a handle on the clinical significance of the ADL vs. IADL distinction, we have to look beyond the textbook definitions and see how these activities actually unfold in the real world. When we compare similar, yet functionally different, tasks side-by-side, it reveals the complex cognitive machinery that independence truly relies on. This kind of nuanced analysis is what helps clinicians spot those subtle but critical shifts in a person's abilities.

Mobility vs Navigating Transportation

A person's ability to walk, or their mobility, is a foundational ADL. At its core, it’s about basic motor skills, balance, and the physical strength needed to move from room to room or simply get up from a chair. It’s absolutely essential, but it's a relatively straightforward physical task.

Using public transportation, however, is a much more demanding IADL. This task requires a whole cascade of cognitive skills working in concert:

Planning: First, the person has to figure out the right bus route and its schedule. For example, they need to use an app or a paper schedule to find which bus goes to their doctor's office.

Executive Function: They need to manage their time to get to the stop, have the correct fare ready, and think on their feet if the bus is running late.

Processing Speed: They have to quickly read signs, listen for stop announcements, and react fast enough to get off at the right time.

Memory: Simply remembering the route and their destination is crucial for the trip to be a success.

Someone might be perfectly mobile inside their home but find the thought of navigating the bus system completely overwhelming. This gap is telling; it shows how IADLs can uncover deficits in higher-order thinking that a simple ADL assessment would almost certainly miss.

Personal Hygiene vs Managing a Household

Taking care of personal hygiene—like bathing or brushing teeth—is another core ADL. These are routine, almost automatic tasks that focus on immediate self-care. They require very little planning and are usually done in a familiar setting.

Managing a household, on the other hand, is a multifaceted IADL that leans heavily on executive functions. It’s about so much more than just cleaning. A person has to be able to:

Organize and Plan: This means creating shopping lists, managing a budget for groceries, and scheduling chores. A practical example is noticing they are low on milk, adding it to a list, and planning a trip to the store before it runs out.

Problem-Solve: They need to figure out how to fix a leaky faucet, handle an unexpected repair, or adapt when a store is out of a key ingredient.

Maintain Safety: This includes recognizing when food has gone bad or when something in the house could pose a risk.

It's common to see someone who can shower independently (ADL) but is no longer able to keep their kitchen safe and stocked (IADL). The latter requires foresight, organization, and judgment—cognitive skills that are often the first to show signs of decline in neurodegenerative conditions. For a deeper dive into how these cognitive domains are formally evaluated, you can explore our guide on what is a neuropsychological assessment.

A key clinical takeaway is that a decline in IADLs often precedes a decline in ADLs. This pattern serves as a critical early warning sign, signalling that underlying cognitive changes are beginning to impact complex daily tasks, even while basic self-care remains intact.

Choosing and Interpreting Assessment Tools

Translating your clinical observations into hard data starts with picking the right assessment tool. For those of us in healthcare, standardized scales are the bedrock of what we do—they give us a consistent, evidence-based way to gauge a person's functional abilities, see how they change over time, and build a care plan that actually works. The real skill isn't just knowing which tool to use, but how to interpret the results within the ADL vs IADL framework.

When you’re looking at the basics of self-care, the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living is a go-to tool. It’s been around for a reason. It cleanly assesses six core ADLs: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding. The scoring is refreshingly straightforward—it ranks a person as either independent or dependent in each area.

For those more complex, higher-order skills, the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale is the industry standard. This scale looks at eight key IADLs, including using the telephone, shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, laundry, getting around, managing medications, and handling finances. Every domain is scored based on how much help someone needs to get it done.

Practical Tips for Administration and Scoring

Running through these assessments is more than a box-ticking exercise. If you want insights you can actually act on, you have to dig a little deeper.

Observe, Don't Just Ask: If you can, watch the patient perform the task. For instance, instead of asking if they can make tea, observe them doing it. Do they remember all the steps? Do they do it safely?

Bring in a Caregiver: A family member or caregiver sees the day-to-day reality. They can offer invaluable context on what's typical performance, what's new, and any safety issues they've spotted.

Probe for the Nuance: Don't just ask, "Can you manage your medications?" Instead, try, "Tell me how you keep track of your pills each day." This opens the door to understanding the cognitive strategies—or the lack of them—behind the task.

Making sense of the scores isn't about the final number. A drop in a specific IADL, like managing finances, often flags a problem with executive function. A new struggle with an ADL like dressing, however, might point to a more advanced stage of functional or cognitive decline. For a closer look at the cognitive screening tools that can help clarify this, check out our detailed comparison of the MoCA vs MMSE.

The real clinical value isn't in the total score, but in the pattern of deficits. A patient who aces the Katz ADL Index but struggles with several IADLs on the Lawton Scale is showing a classic early-warning sign of cognitive impairment.

This pattern isn't just anecdotal; it shows up in the population data. According to Statistics Canada, 10.2% of seniors have trouble with basic ADLs, but almost double that number—19.7%—struggle with IADLs. This gap really drives home why assessing IADLs early is so critical. It's also central for professionals using tools like Orange Neurosciences, which profiles executive function and processing speed to flag these risks before they turn into crises.

You can dive into the findings from the 2021 Census Dictionary on Statistics Canada's website. Ultimately, translating these scores into a meaningful care plan is about targeting the specific deficits you find, which is the only way to create a truly personalized intervention.

Applying ADL and IADL Assessments in Clinical Practice

Knowing the difference between ADLs and IADLs is one thing, but using that knowledge to build care plans that actually work is another beast entirely. The real skill is bridging that gap from theory to practice, letting these assessments truly guide your clinical decisions. Case studies are perfect for this, offering a clear framework for seeing how assessment scores translate into tailored, effective interventions.

Let’s walk through a couple of real-world scenarios. By doing so, we can see how the ADL vs. IADL distinction plays out on the ground and helps us create meaningful, person-centred care that hits the mark.

Case Study One: Early Cognitive Decline

Meet Eleanor, a 78-year-old retired teacher who lives on her own. Her family started noticing some subtle changes that have them worried. While Eleanor handles all her personal care (ADLs) just fine—bathing, dressing, and getting around her house aren't an issue—she’s been missing appointments and bills are starting to pile up, unpaid.

We ran an assessment using the Lawton IADL Scale, and it immediately flagged a few specific problems:

Financial Management: Eleanor, who used to be meticulous with her finances, is now struggling to track expenses and has forgotten to pay several bills.

Transportation: She recently got lost while driving to the grocery store, a route she knows like the back of her hand. Now, she's relying more and more on her family.

Medication Management: Her pill organizer is often a mess, with doses either missed or accidentally doubled.

These aren't just minor slip-ups; they point toward an early cognitive impairment that's hitting her executive functions hard.

The actionable insight here is that Eleanor doesn't need help with personal care, but requires immediate support for her IADLs to remain safe at home. Our care plan includes: setting up automatic bill payments, arranging for a pre-filled weekly medication dispenser from the pharmacy, and scheduling a reliable ride service for her appointments. These assessments are vital for understanding when assisted living is needed, especially when managing IADLs becomes a safety risk.

Case Study Two: Post-Stroke Rehabilitation

Now, let's look at Robert, a 65-year-old who is recovering from a moderate stroke. Physically, he’s bounced back remarkably well. His Katz ADL Index score is perfect—he can walk, eat, and manage his hygiene without any help. The stroke, however, left its mark on his cognitive processing speed and short-term memory.

His IADL assessment tells a very different story:

Meal Preparation: Robert can't follow a recipe with multiple steps anymore. He often forgets ingredients or, worse, burns the food.

Communication: Using his smartphone has become completely overwhelming, causing him to miss important calls from his healthcare team.

Housekeeping: He just doesn’t have the organizational skills to keep his home clean and safe.

Robert’s case is a classic example of intact ADLs masking significant IADL deficits. His functional independence is compromised not by physical limitations, but by cognitive ones.

This is more common than you might think. Stroke best practices show that while around 70% of patients maintain their ADLs, they can initially lose 50% of their IADL capacity. The good news is that this deficit is often recoverable with targeted cognitive rehab, which just goes to show how critical an early IADL assessment really is.

Robert's care plan zeroes in on these cognitive gaps. The actionable plan includes occupational therapy using simplified, picture-based recipes to rebuild cooking skills, speech therapy focused on using voice commands on his smartphone, and a checklist system for daily chores. In complex situations like this, knowing the role of qualified capacity assessors in Ontario is crucial for getting formal evaluations done right. These examples really drive home how a precise IADL assessment directly shapes effective rehabilitation goals and the entire support structure around a patient.

Connecting Functional Assessment to Cognitive Profiling

Functional assessments like ADL and IADL scales are fantastic for showing us what a person is struggling with day-to-day. They’re great at flagging specific tasks, from handling finances to personal hygiene, where someone's independence is starting to slip. But these tools alone often leave a huge question hanging in the air: why is this happening?

If you want to move your clinical practice from simple observation to a truly data-driven diagnosis, you have to connect the dots between functional assessment and cognitive profiling. Making this link is how you get past the symptoms and start targeting the root cause of functional decline, which is the secret to creating care plans that actually work.

Uncovering the Why Behind Functional Decline

When someone has a hard time with an IADL like making a meal or managing their medication, the problem is rarely just a physical one. These complex tasks are heavily dependent on specific cognitive domains. A drop in IADL performance is often a direct mirror of underlying cognitive deficits.

Executive Function: When planning a budget, following a recipe, or organizing a shopping list becomes a struggle, it often points to issues with executive functions.

Memory: Forgetting appointments, messing up medications, or getting lost in familiar territory are classic signs that memory is impaired.

Attention and Processing Speed: Not being able to focus on paying bills or feeling totally overwhelmed by taking public transit can signal problems with attention and slower processing speed.

By figuring out which cognitive domain is impaired, you can design interventions that get to the core of the problem. For example, instead of just simplifying meal prep for a client (addressing the what), you can introduce cognitive exercises that specifically target their weakened executive functions (addressing the why). This is the key to creating truly actionable care plans.

From Observation to Objective Data

Subjective reports from clients and their families are valuable, no doubt. But they can also be skewed by a lack of insight or even a person's desire to appear more capable than they are. This is where objective cognitive data becomes absolutely essential. Today's tools make it possible to get a clear, unbiased picture of a person's cognitive health, quickly and efficiently.

The real power in modern assessment comes from pairing functional observation with objective cognitive data. This combination allows you to validate your clinical intuition, benchmark a patient's baseline, and track their progress with undeniable evidence.

This is exactly where Orange Neurosciences’ AI-powered platform comes in. It provides that critical link, delivering a comprehensive cognitive profile in under 30 minutes that measures key domains like attention, memory, and executive function. This fast, precise data gives you the power to understand the cognitive drivers behind the IADL challenges you're observing. Tools like our OrangeCheck offer a reliable way to benchmark cognitive function and see how it changes over time in response to your interventions. You can explore our full suite of cognitive assessments to see how they can fit into your workflow.

When you connect functional assessments to robust cognitive profiling, you gain the insights needed to craft truly personalized care plans. This data-driven approach doesn't just improve patient outcomes; it also gives you a clear, defensible rationale for your clinical decisions.

Your Questions About Functional Assessments, Answered

When you're navigating the world of ADLs and IADLs, a lot of questions can come up for clinicians and families alike. We've put together some straightforward answers to the most common ones to help you understand the key concepts and what they mean in practice.

When Does an IADL Decline Mean It's Time for a Cognitive Assessment?

Any noticeable slip in one or more IADLs, especially if it’s a clear change from how a person used to function, is a big red flag. A practical example is when someone who was always on top of their finances suddenly starts struggling with bills, or a meticulous planner can no longer manage their medications. These aren't just one-off mistakes; they are patterns that signal a need to look deeper.

A full cognitive assessment is a must when IADL struggles start to compromise a person's safety or independence. Forgetting where you put your wallet after a shopping trip is one thing. But if someone can no longer put together a budget or consistently misses bill payments, you're looking at a much bigger issue.

Catching these things early with a good screening tool gives you the objective data needed to decide if a complete neuropsychological workup is the next step. Being proactive here helps pinpoint the root cause of the functional challenges, preventing critical delays in getting the right diagnosis and support in place.

Can Someone Have Intact ADLs but Impaired IADLs?

Absolutely. In fact, it’s an incredibly common scenario, especially in the early stages of cognitive decline. The basic skills for self-care (ADLs) are often some of the last to go because they're such deeply learned, almost automatic, behaviours.

On the other hand, IADLs lean heavily on higher-level cognitive skills like planning, organizing, and problem-solving. A practical example is seeing a loved one who can still get dressed and ready for the day without any trouble but can't follow a simple recipe anymore. This is a classic sign of an underlying cognitive shift and is exactly why understanding the ADL vs IADL difference is so crucial for early detection.

How Can Technology Help Track ADL and IADL Performance?

Technology provides a powerful, objective lens to see how a person's functional abilities are changing over time. Instead of relying purely on subjective reports, digital platforms can actually measure the specific cognitive skills that make IADLs possible.

Objective Benchmarking: By regularly assessing things like processing speed, memory, and executive function, clinicians can spot subtle declines long before they become a full-blown functional crisis.

Engaging Monitoring: Game-based assessments offer a more engaging way to keep an eye on cognitive health, generating valuable real-time data without feeling like a test.

Informed Care Planning: This data is gold for care planning. It allows for quick, targeted adjustments to support plans and gives everyone clear benchmarks to see if interventions are actually working.

To truly understand what's going on, you have to connect what you're observing in daily life to objective cognitive data. Orange Neurosciences offers the tools to bridge that gap, delivering fast, precise cognitive profiles that get to the why behind a functional decline. Find out how our AI-powered platform can fit into your practice and empower you with the insights to make better, faster care decisions. Visit our website at https://orangeneurosciences.ca or email us to schedule a demo and see these actionable insights for yourself.

Orange Neurosciences' Cognitive Skills Assessments (CSA) are intended as an aid for assessing the cognitive well-being of an individual. In a clinical setting, the CSA results (when interpreted by a qualified healthcare provider) may be used as an aid in determining whether further cognitive evaluation is needed. Orange Neurosciences' brain training programs are designed to promote and encourage overall cognitive health. Orange Neurosciences does not offer any medical diagnosis or treatment of any medical disease or condition. Orange Neurosciences products may also be used for research purposes for any range of cognition-related assessments. If used for research purposes, all use of the product must comply with the appropriate human subjects' procedures as they exist within the researcher's institution and will be the researcher's responsibility. All such human subject protections shall be under the provisions of all applicable sections of the Code of Federal Regulations.

© 2025 by Orange Neurosciences Corporation