A Practical Guide to the Dementia Clock Test

Nov 12, 2025

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is a surprisingly simple yet powerful screening tool that clinicians use to get a quick read on potential cognitive changes, especially those linked to dementia. It’s a pen-and-paper test that assesses critical cognitive domains like executive function and visuospatial skills just by asking someone to draw a clock showing a specific time.

Understanding the Dementia Clock Test

At its heart, the Clock Drawing Test is a straightforward request with profound clinical implications. A clinician will hand a person a blank sheet of paper and ask them to draw a clock face, fill in all the numbers, and then set the hands to a specific time—usually "10 minutes past 11."

This simple direction kicks off a complex mental workout. To draw the clock correctly, the brain has to juggle several demanding tasks at once:

Planning and Organization: The person must visualize and plan the clock's layout, ensuring the numbers are spaced out properly around the circle. Practical example: Deciding where to place the "12" and "6" first to anchor the drawing.

Visuospatial Skills: This is all about accurately perceiving and then drawing the round clock face and placing the numbers and hands in the right spots.

Abstract Thinking: It requires understanding that a clock is a symbolic representation of time and that the two hands have very different jobs. Practical example: Knowing the short hand represents the hour and the long hand represents the minutes.

Executive Function: This is the brain’s "project manager," overseeing the entire process from the initial instruction to the final drawing.

This is exactly why the CDT is so valued in clinical settings. It provides a rapid snapshot of cognitive areas that are often the first to be impacted by dementia. It’s far less about artistic talent and much more about the underlying cognitive processes. You can learn more about this area of practice by exploring our guide on what is cognitive assessment.

Why "10 Past 11" Is the Standard

Ever wonder why that specific time? Setting the hands to "10 past 11" is a deliberate choice designed to be challenging. It forces the individual to place the minute and hour hands in two separate visual quadrants of the clock, which engages both hemispheres of the brain. A simpler time, like 6:00 or 3:00, just wouldn’t put the same kind of stress on these cognitive functions.

The CDT's clinical validity has been well-established in Canadian dementia screening. Research from Toronto's Baycrest Health Sciences has shown that the test can achieve sensitivity and specificity rates of around 85% when used as part of a broader assessment. This work also cemented "10 past 11" as the most effective time setting for spotting cognitive issues in Canadian clinical practice.

The real beauty of the clock test is its simplicity. It’s a low-stress, non-intimidating way for a doctor to get a quick, valuable look into a patient’s cognitive health during a routine visit.

A Real-World Clinical Scenario

Let's picture Arthur, a 78-year-old man, at his family doctor's office. His daughter has mentioned he’s been getting more forgetful. As a quick screen, the doctor asks Arthur to draw a clock showing "10 past 11."

Arthur draws a neat circle. But then he crams all the numbers into the right side of the clock, between 12 and 6. For the hands, he draws both pointing directly at the 11.

Actionable Insight: This single drawing offers immediate, valuable clues. The poor number spacing points to potential visuospatial planning problems, while the incorrect hand placement suggests a struggle with abstract thought. This isn't a diagnosis, but it's a clear signal that a more in-depth cognitive evaluation is needed. To better understand the context, it helps to be familiar with the early signs of dementia.

How to Administer the Dementia Clock Test

Getting a reliable result from the dementia clock test is all about standardized administration. The goal is to create a calm, controlled space where the individual can focus without feeling stressed or judged, allowing for accurate observation.

First, seat the person comfortably in a quiet room with good lighting and few distractions. Hand them a blank sheet of paper and a pen or pencil. The words you use next are critical—they must be precise and consistent to keep the test standardized.

Setting Up the Test Environment

Start with simple, clear instructions. Avoid complex sentences that could cause confusion. A practical, step-by-step approach is best.

Actionable Script:

Say, "I would like you to draw a clock for me. First, please draw a large circle."

Once they’ve drawn the circle, say, "Now, please put all the numbers in the correct places on the clock face."

After that's done, give the final instruction: "Finally, please set the hands to show the time '10 minutes past 11'."

This command-style approach breaks the task down into manageable pieces without giving away hints.

The real value comes not just from the final drawing, but from observing the process. Note any hesitation, self-corrections, or frustration. These behaviours can be as revealing as the finished clock.

Key Observations During the Test

Watching how someone tackles this task gives incredible insight. Experienced clinicians are trained to spot subtle behaviours that might point to underlying cognitive challenges.

Actionable Checklist:

Initial Hesitation: Does the person pause for a long time before starting? This could signal difficulty with planning.

Number Placement Strategy: Do they place "anchor numbers" (12, 6, 3, 9) first, or do they place them sequentially? Going in order often leads to spacing errors.

Perseveration or Repetition: Do they repeat numbers or draw the hands multiple times? This can be a sign of issues with cognitive flexibility.

Looking for Cues: Does the person glance at a real clock or their watch? This reliance on an external aid is an important observation.

While this guide provides a framework, formal interpretation is best left to trained professionals. If you're a clinician interested in exploring a wider range of screening tools, learn more about the comprehensive cognitive assessments available on our website.

Scoring and Interpreting Clock Drawing Results

Once the clock is drawn, the real work begins. A completed clock drawing is more than a picture; it’s a detailed story about a person's cognitive abilities. It can reveal significant clues about executive function, memory, and visuospatial planning.

When scoring, you’re not looking for artistic talent. You're looking for specific errors that point to potential neurological challenges. Most scoring systems focus on a few key elements: a closed circle, all 12 numbers present and in the right order, reasonable spacing, and correct hand placement for "10 past 11."

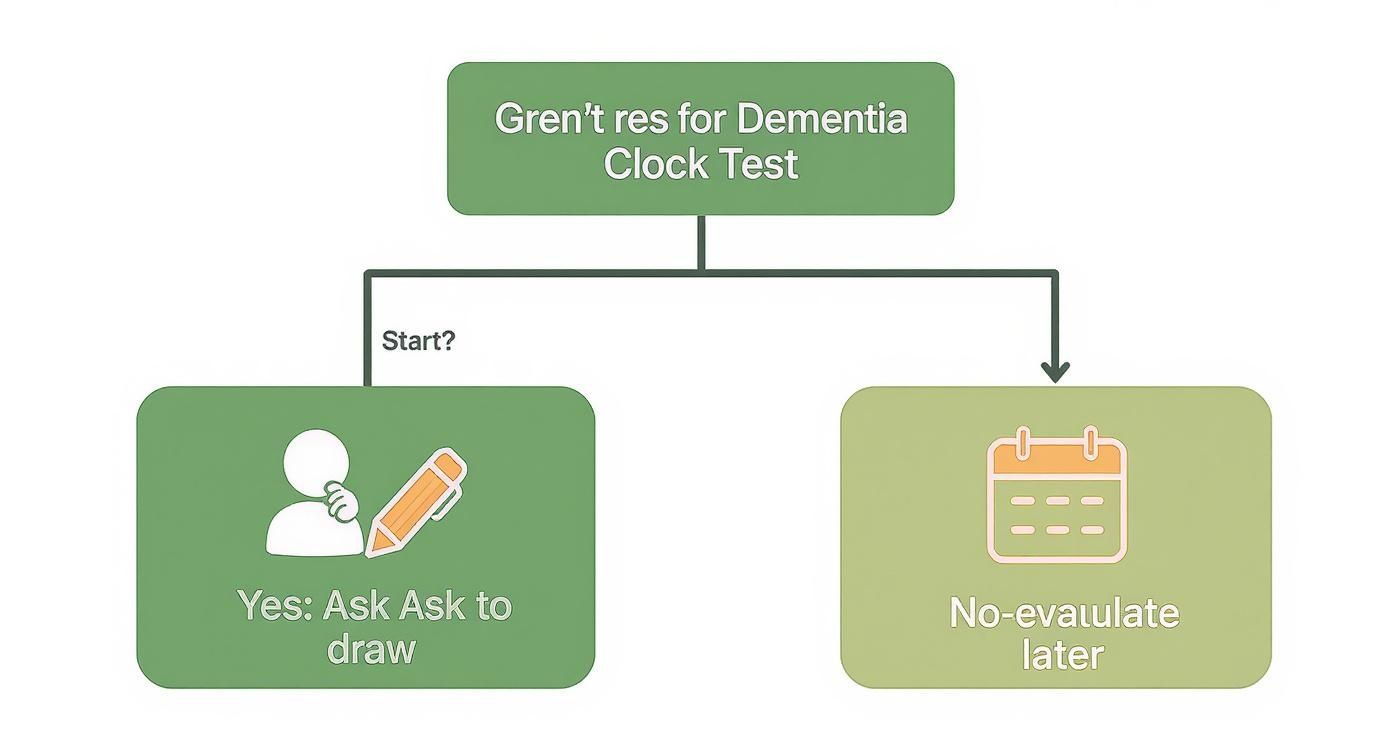

This decision tree visualizes the initial steps in using a dementia clock test, guiding the decision-making process for screening.

As you can see, the first crucial step is deciding if the test is appropriate. This leads to either administering the test or postponing it.

Translating Errors into Clinical Insights

Specific mistakes often correlate with particular cognitive deficits. This test gives a neurologist a visual tool to explain a complex situation to a family in an easy-to-grasp way.

Practical Example: A neurologist sits with a family, showing them their loved one's drawing. The clock face is well-formed, but all the numbers are crammed on the right side. The neurologist might explain, "This bunching of the numbers suggests a potential issue with visuospatial planning, managed by a specific part of the brain. It's not about vision, but how the brain creates a mental map of space."

Other common red flags include:

Conceptual Errors: Writing "ten past eleven" instead of drawing the hands can indicate a struggle with abstract thought.

Perseveration: Drawing more than 12 numbers can signal problems with cognitive flexibility.

Incorrect Hand Placement: Both hands pointing to the 10 shows difficulty differentiating the roles of the hour and minute hands.

The Mini-Cog: A Broader Perspective

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is a powerful screener, but it's even more effective when paired with other tools. It's a key component of the Mini-Cog, a quick, two-part assessment that combines the clock drawing with a simple three-word recall task.

Combining these two elements creates a much more robust screening score. For instance, someone who struggles with word recall but draws a normal clock has a different cognitive profile than someone who aces recall but produces an abnormal drawing.

This integrated approach helps clinicians build a more complete picture. For a deeper dive into comprehensive assessments, check out our guide on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment instructions.

This simple table shows how the two parts of the Mini-Cog work together.

Mini-Cog Scoring Framework

3-Word Recall Score | CDT Result | Actionable Insight |

|---|---|---|

0 | Normal or Abnormal | Cognitive impairment likely. Further assessment needed. |

1-2 | Abnormal | Cognitive impairment likely. Further assessment needed. |

1-2 | Normal | Cognitive impairment unlikely. Monitor and re-assess as needed. |

3 | Normal or Abnormal | Cognitive impairment unlikely. |

By looking at both memory and visuospatial components, you get a clearer signal for whether a more detailed evaluation is needed.

"A clock drawing provides tangible evidence. For families, seeing the drawing can make the reality of cognitive change more concrete than simply hearing a test score."

Here in Canada, dementia screening guidelines from organizations like the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) have embraced the CDT as a quick first-line tool. Often, the scoring is a straightforward pass/fail; an abnormal clock immediately flags the need for more evaluation.

Knowing When the Clock Test Is Not Enough

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is a fantastic first-line screening tool, but it's vital to know its limits. A perfectly drawn clock doesn't always mean everything is fine, especially when looking at very mild cognitive impairment.

Its real strength is in assessing visuospatial and executive functions. But cognition is far more complex than just those two areas.

Think of it like checking a car's tires. If they look good, that's positive, but it tells you nothing about the engine. A normal clock drawing can easily miss subtle problems in other critical cognitive areas.

Moving Beyond a Single Metric

This is where a more thorough evaluation becomes necessary. Someone in the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, for example, might still have the cognitive chops to draw a perfect clock while struggling with significant short-term memory loss—an area the CDT doesn't directly touch.

Practical Scenario: A patient, Margaret, completes the clock drawing task flawlessly. Her numbers are spaced perfectly, and the hands point exactly to "10 past 11." On the surface, it looks like a pass.

But then, the clinician administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The MoCA digs deeper into attention, language, abstract thinking, and memory recall. During the MoCA, Margaret is asked to remember five simple words. A few minutes later, she can't recall a single one.

Actionable Insight: This discrepancy is a classic red flag. The perfect clock showed her visuospatial skills were intact, but the failed memory task from the MoCA revealed a significant deficit the clock test alone would have missed.

Highlighting the Need for Broader Assessment

This example drives home why relying on a single test can be misleading. Cognitive assessment is about building a complete picture of a person's cognitive strengths and weaknesses. The MoCA's ability to probe different cognitive domains makes it a more sensitive tool for catching subtle changes.

For a deeper dive into other specialized assessments, you can explore our guide on the Frontal Assessment Battery, which specifically targets executive functions.

Recent Canadian neurological research has underscored the MoCA's superior value in certain high-risk groups. One study found that for patients with a condition increasing dementia risk, the MoCA was highly effective at predicting who would develop dementia, while the CDT offered no useful screening value for this specific group. This reinforces the need to pick the right tool for the job.

The Future of Digital Clock Drawing Tests

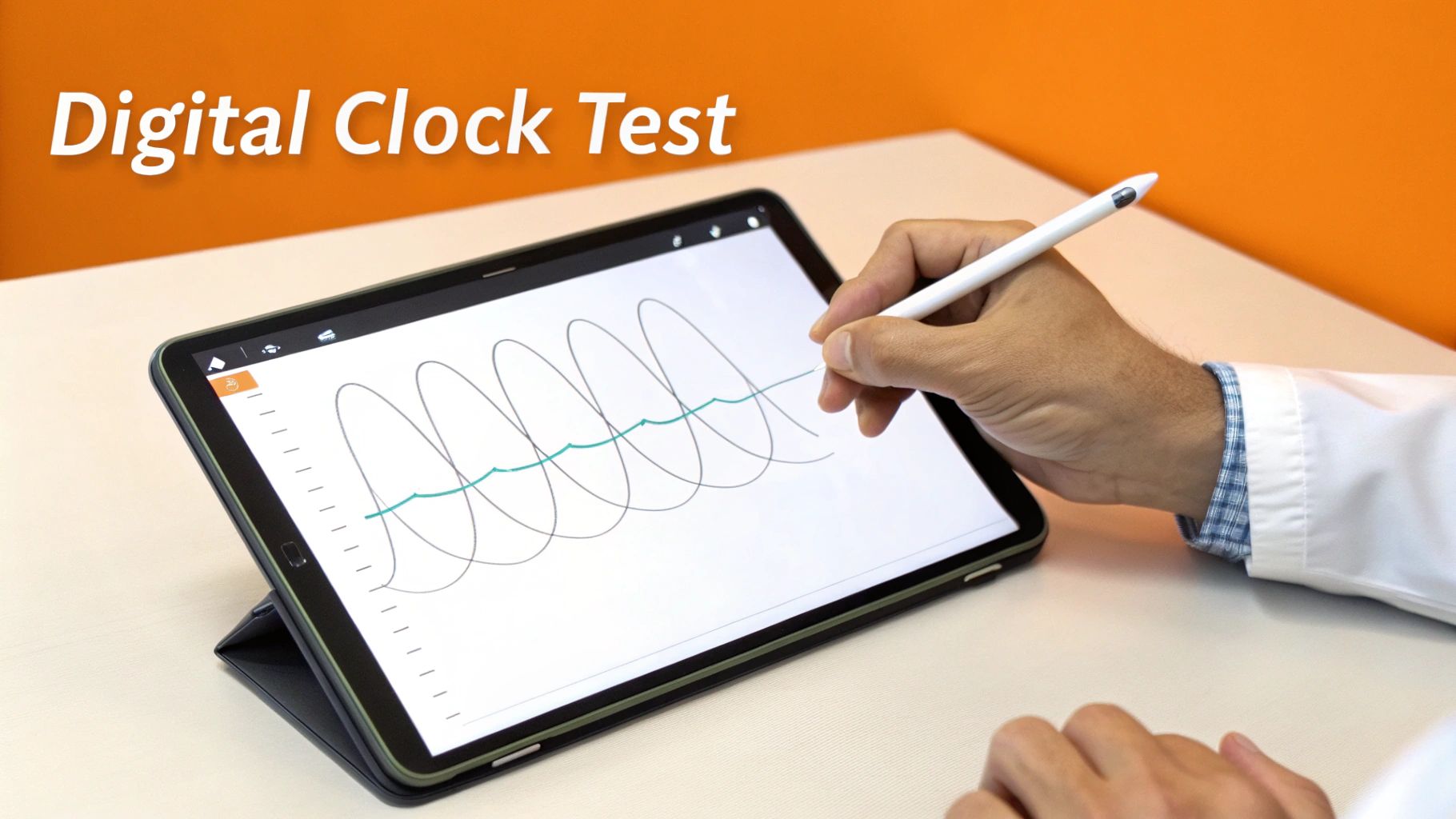

The classic pen-and-paper clock test has been reliable for years, but its next evolution is transforming clinical practice. Digital platforms take this assessment and layer on data that was previously invisible, giving us a richer, more detailed picture of cognitive processing.

Digital versions bring automated, objective scoring, which sidesteps the subjectivity of manual interpretation. A digital system scores based on precise algorithms, ensuring every test is measured with the same reliable yardstick.

The real game-changer is the analysis of drawing kinematics—all the information captured while the person is drawing.

Uncovering Deeper Cognitive Insights

Drawing kinematics gives us a moment-by-moment replay of how someone completes the task. It includes metrics impossible for a human observer to measure accurately.

Actionable Data Points:

Latency to start: How long did the person hesitate before making the first mark?

Drawing speed: The velocity and fluidity of their pen strokes can point to issues with processing speed.

Pauses and hesitations: The exact length and frequency of pauses can reveal deficits in planning.

Pen pressure: Variations in pressure could correlate with the amount of cognitive effort being exerted.

This granular data lets us see not just what the patient drew, but how they drew it. A patient might produce a clock that looks fine, but kinematic data could show they took an unusually long time, with multiple hesitations, signalling an underlying cognitive strain we would have otherwise missed.

Digital clock tests turn the assessment from a static snapshot into a dynamic video. This detailed process data provides a more sensitive and nuanced view of brain health, helping spot subtle changes much earlier.

Adopting Digital Workflows in Your Clinic

Making the switch to a digital workflow can dramatically improve efficiency and data quality. A traditional test requires finding a quiet space, gathering materials, manual timing, and subjective scoring.

A modern digital assessment streamlines this process. Run on a tablet, instructions are delivered consistently, and scoring is instantaneous and objective. The results are automatically saved to the patient’s file, ready for review and for tracking changes over time.

This technology empowers clinics to screen more patients with greater accuracy. To see how these modern tools fit into a clinical setting, explore our overview of cognitive assessment online.

Your Questions About the Clock Test, Answered

Navigating cognitive assessments brings up questions. Here are some clear, practical answers to common queries about the dementia clock test.

Why Is the Time '10 Past 11' Always Used?

That specific time—"10 past 11"—is a clever and crucial part of the test.

Asking for 11:10 forces a person to process numbers on opposite sides of the clock face. This simple command requires both hemispheres of the brain to coordinate, testing complex skills like planning and visuospatial reasoning. A simpler time, say 3:00, wouldn't challenge those mental processes in the same way, making 11:10 better at picking up on subtle cognitive deficits.

Can Someone with Dementia Draw a Perfect Clock?

Yes, absolutely. It's possible for someone in the early stages of dementia to draw a perfect clock. While a flawless drawing is a good sign, it does not definitively rule out cognitive impairment.

Actionable Takeaway: The clock test is a screening tool, not a diagnostic one. If other symptoms are present, a normal clock drawing is just one piece of the puzzle. It should prompt a more comprehensive evaluation with tools like the MoCA to get the full picture.

Can I Administer the Clock Test to a Family Member?

While you can ask a loved one to draw a clock, this should never be a do-it-yourself diagnosis. The test's clinical value comes from standardized administration and interpretation by a professional.

A Better Approach: Use the drawing as a gentle conversation starter. If the clock your loved one draws is worrying, bring the actual drawing to their next doctor’s appointment. This gives the physician tangible information to start a proper evaluation. In the meantime, exploring brain exercises for seniors can be a wonderfully proactive way to support their cognitive health.

At Orange Neurosciences, we are committed to advancing brain health through precise, objective cognitive assessments. Our AI-powered platform delivers deep insights that go far beyond traditional screening, helping create clearer, faster pathways to effective care. Ready to see how our tools can support a comprehensive cognitive evaluation at your practice? Visit us at https://orangeneurosciences.ca or contact our team today for a demonstration.

Orange Neurosciences' Cognitive Skills Assessments (CSA) are intended as an aid for assessing the cognitive well-being of an individual. In a clinical setting, the CSA results (when interpreted by a qualified healthcare provider) may be used as an aid in determining whether further cognitive evaluation is needed. Orange Neurosciences' brain training programs are designed to promote and encourage overall cognitive health. Orange Neurosciences does not offer any medical diagnosis or treatment of any medical disease or condition. Orange Neurosciences products may also be used for research purposes for any range of cognition-related assessments. If used for research purposes, all use of the product must comply with the appropriate human subjects' procedures as they exist within the researcher's institution and will be the researcher's responsibility. All such human subject protections shall be under the provisions of all applicable sections of the Code of Federal Regulations.

© 2025 by Orange Neurosciences Corporation